After visiting the Polish capital of Warsaw, Mark Bibby Jackson takes the train to Łódź, the Manchester of Poland, and finds himself unexpectedly moved.

I knew something of the Warsaw Ghetto before my recent visit there – although the amazing POLIN Museum proved how vast my ignorance was – however, as regards the Łódź Ghetto, I was totally ignorant.

So, I really did not know what to expect on my trip to the Jewish Cemetery on the second day of my visit to the Manchester of Poland.

Jewish Influence in Łódź

The previous day, my guide Aleksandra Ciach (Alex) had explained the massive influence the Jewish community had on the development of the city.

Łódź rose to prominence in the 19th century due to its cotton mills and factories – hence the Manchester of Poland moniker. One of the most important industrialists was Izrael Poznański, whose former spinning mill complex has been converted into the modern arts and retail park Manufaktura. Poznański is regarded as one of the three ‘Kings of Cotton’ in Łódź, along with Ludwik Geyer and Karol Scheibler.

In 1900, there were some 850 textile plants in the city and by the start of the First World War I, Łódź was the fastest growing city in Europe with a population of 300,000 to 400,000.

Before the Second World War, one of three inhabitants were Jewish. Just like in Warsaw, the Jews were herded into a ghetto by the Nazis. The Łódź Ghetto was the second largest in Poland and contained more than 160,000 people when the gates closed on 30 April 1940. It was also the last ghetto to be liquidated, in August 1944, absorbing Jews from across Europe who were used as slave labour.

Starting early 1942, the ghetto’s inhabitants were transported to Chelmo (or Kulmhof) extermination camp, 70-80 kilometres to the northwest of the city. It is estimated that 150,000 to 180,000 were killed there. When the Russian troops liberated Łódź, 877 people remained hiding in the ghetto.

Jewish Cemetery Łódź

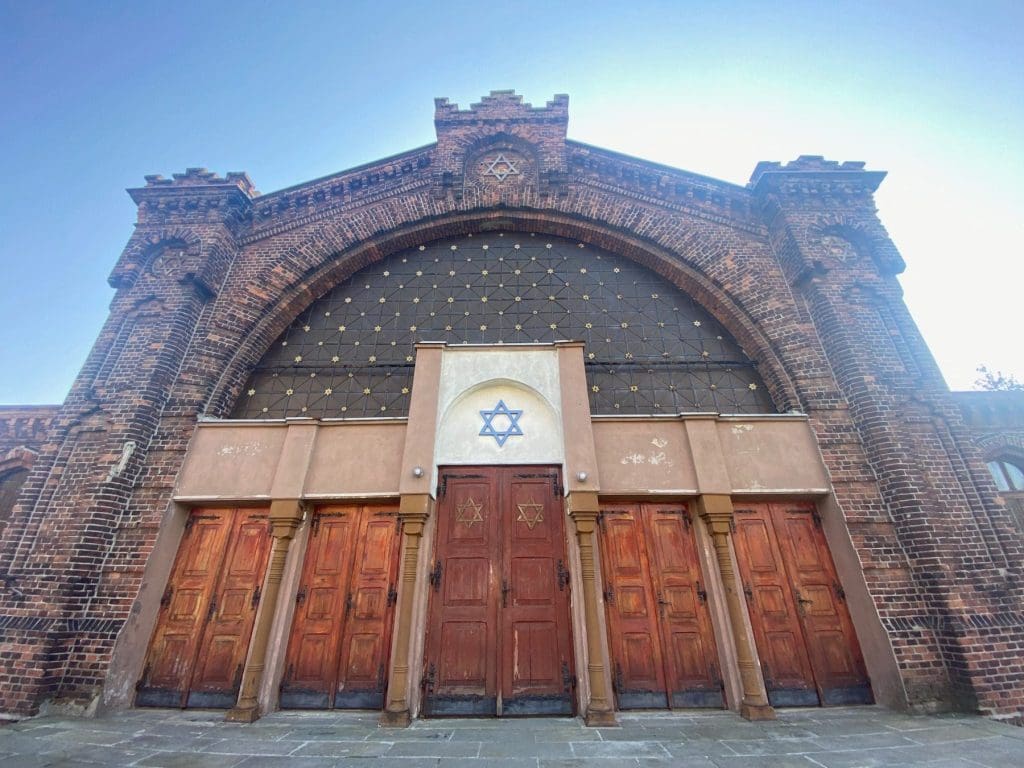

The cemetery was created in 1892 on land donated by Poznański, at which time it was the largest Jewish necropolis in Europe. The impressive funeral home (Beit Tahara) was competed six years later. Alex says it was the largest of its type in the world. From here we walk to Poznański’s family tomb, naturally the largest structure in the graveyard. It certainly stands out.

Next to the cemetery is a massive ghetto field where 43,527 Jews who died in the Łódź ghetto between February 1940 and August 1944 are buried. Standing in the open field, with small markings signifying where the bodies lie, is a moving experience. It reminds me of the Fields of Flanders.

The graveyard has been cleared, but is starting to become overgrown again, as though nature is reclaiming its land. Close to the funeral home, is a wall with the names of those whose bodies could not be found, or of Łódź Jews who were buried elsewhere. One of the names is Dawid Sierakowiak, who kept a dairy from June 1939 until shortly before his death officially from tuberculosis / lung failure, although he might well have died from starvation, in August 1943, shortly after his 19th birthday.

Extracts from his dairy illuminate what life was like in the ghetto.

On 20 May 1942, he wrote, “We are not considered humans at all; just cattle for work or slaughter. No one knows what happened to the Jews deported from Łódź. No one can be certain of anything now.”

On another occasion, he wrote, “All I care is that there is soup in my workshop.”

Although, his name is listed on the wall of the missing, his body was eventually discovered, and a tombstone now marks the grave of the Anne Frank of the Łódź Ghetto.

Walk Along Piotrkowska Street

Perhaps the most famous Jew to be born in Łódź was Arthur Rubinstein, who is widely regarded as one of the best pianists of the twentieth century. He is one of the many people celebrated with statues along Piotrkowska Street, the main street in Łódź, along which I walked the previous day with Alex. Another is the poet Julian Tuwim, who has a statue sitting on a bench outside the Town Hall.

Although Łódź rose to prominence in the 19th century due to its cotton mills, it was granted city status in 1423. At 4.2-km long Piotrkowska Street is apparently the longest shopping street in Europe. One of the most interesting buildings is Gutenberg House, which was built in 1896. This amazing example of neo-Gothic architecture was voted the most beautiful building in the Łódź.

The street is an eclectic mix of styles, reflecting taste and culture. Classical French stands next to wonderful art nouveau. Łódź is also noted for its street art. One of which is the amazing courtyard of Wojciech Siudmak, which was inspired by Dune. Another is Rose Passage made of broken mirrors designed by Joanna Rajkowska, the artist whose amazing Eye photograph can be seen at the POLIN Museum in Warsaw. She is also the designer of the Palm statue in Polish capital. Rose Passage leads from Piotrkowska Street towards Manufaktura, linking the old and new city centres.

Łódź Manufaktura: Manchester of Poland

Built between 1877 and 1878 by Israel Poznański, Manufaktura was the industrial heart of Łódź in the latter part of the 19th century. The industrial complex suffered greatly from World War I and then was looted by the Nazis in the Second World War, and subsequently nationalised. It closed in 1997, but reopened as a major arts centre, shopping mall and leisure complex in 2006.

Łódź Manufaktura has more than 300 stores, restaurants, cafés and pubs in its malls. There is also a multiplex cinema, bowling alley, climbing wall and fitness club, as well as the MS2 branch of The Museum of Art in Łódź and the recommended Muzeum Fabryki Factory Museum, which is on the European Route of Industrial Heritage. Here we saw one of the old mechanical looms in operation.

Next to Manufaktura is Izrael Poznański Palace, which was built on the site of an old tenement building and is an amazing example of flamboyant Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Baroque architecture. Sadly, it was only completed in 1903, so Poznański who died three years earlier would never see his finished palace. Now, the building houses the Museum of the City, and has an interesting room devoted to Arthur Rubinstein.

EC1 – Centre of Science and Technology

My main reason for visiting Łódź was to see how the city has regenerated itself since the demise of its industrial glory. As such Manufaktura is a leading light of how this can be achieved, not only in Poland but in Europe. But it is by no means alone.

After Izrael Poznański Palace, we visited EC1, which in 1907 was the first thermal power plant in the city. Although it was shut down in 2000, it now houses the Science and Technology Centre, which judging from our trip is very popular with kids.

In the evening we dined at OFF Piotrkowska, a unique project bringing together entrepreneurs from creative industries, which was built in the cotton factory of Franciszek Ramisch and Józef John’s iron foundries, just off Piotrkowska Street. Here you can find workshops of fashion designers and architects, clubs, restaurants, exhibition spaces, rehearsal rooms and, on our visit, excellent food.

Film Museum of Cinematography in Łódź

The other main reason for visiting Łódź was to understand more about its connection with cinema. I stayed at Stare Kino, literally ‘old cinema’, a hotel and residence just off Piotrkowska Street, which was the site of the first cinema in Poland – although it was part of the Russian Empire at the time. Called the Chamber of Illusion, it was opened by the Krzeminscy brothers in 1899. Films are still screened here. Each room is designed after a film or film star. My room had a massive poster of Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck in Roman Holiday.

The city is known for the Łódź Film School. Founded in 1948, it includes another Roman, Polański, as one of its alumni. During our visit the school was not open to the public (although it has subsequently opened), so after our visit to the Jewish Cemetery, we went to the Museum of Cinematography as part of Museum of the City. Created in 1976 this became an independent institution moving to the former palace of Karol Scheibler, who came to Łódź from his native Germany in the 1850s, a decade later.

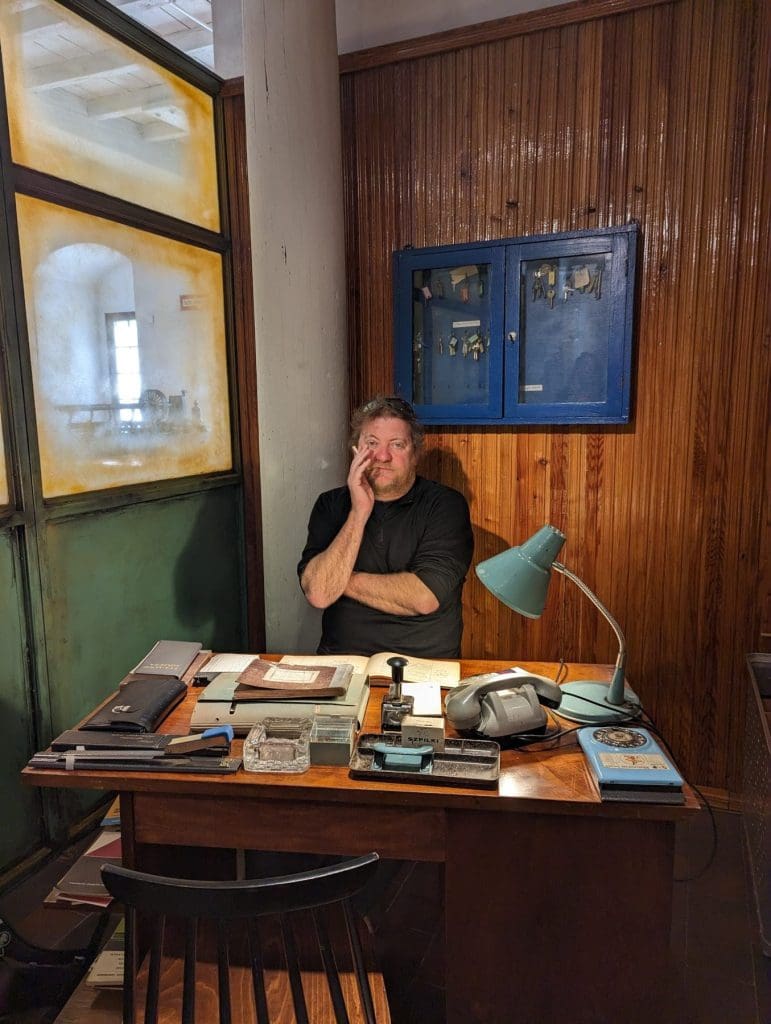

We had a tour of the palace, which is far more understated than that of Poznański, although no less rewarding for it, before visiting the museum. This gave me an exhaustive knowledge of Polish cinema, which I am afraid I promptly forgot, the highlight of which was seeing the Kaiser Panorama, which had interesting photographs of Asia.

Tour of Księży Młyn and Central Museum of Textiles

Despite its industrial history, Łódź is quite a green city. Following the museum, we had lunch in Springs Park next to Scheibler’s Palace. It was wonderful to have a salad sitting outside in the spring sun, while playing hide the food with the pigeons.

From here we could walk to our next destination, the Księży Młyn, Scheibler’s former cotton mill, which was built from the 1860s to 70s, and has now been converted into luxury apartments, as well as the home to the Belgian consulate, as the German industrialist actually carried a Belgian passport.

Next to the mill, the former worker’s cottages have been turned into low-income housing, which was according to Alex, the first revitalisation project in the city. It has a very northern industrial England feel to it, and was featured in the BBC miniseries Bells of War.

Beside Księży Młyn is Herbst Palace, a neo-Renaissance villa built in the 1870s by Scheibler as a wedding present for his daughter Matilda and her husband Edward Herbst who was a manager at the mill. The palace has now become a museum with a wonderful garden. The adjoining Museum of Art of Łódź has an interesting collection of Polish paintings on display.

Our final visit was to the Central Museum of Textiles, located in Ludwik Geyer’s White Factory. It has a mechanical loom from the Poznanski Factory, as well as some interesting exhibitions including one on fashion in Poland.

Outside, there is a model open air museum with real houses that have been moved here. These represent the way that architectural styles have evolved over the decades. The first house was built around 1860 in the city centre while there is an apartment dating back to the 1970s and 80s, set at Christmas Eve, which was a fascinating study of the time.

My visit to Łódź concluded at Monopolis, a cultural complex created in a former distillery, which produced vodka for more than a century from 1902. Another great example of mixed-use conversion of former industrial sites, Monopolis has a couple of theatres, where you can see open-air concerts, and art galleries, as well as a small museum devoted to the distillery. This is to be our last supper in Łódź – a most interesting city, which shows how industrial heritage can form the basis of major urban regeneration, paving the way for the growth of tourism.

How To Get to Łódź

It is really easy to travel to Łódź Fabryczna station by train. The journey time from Łódź to Warsaw and vice versa is about an hour-and-a-half.

Łódź Pronuciation

One of the hardest things about visiting Łódź is working out how to pronounce the word. The key thing is that the first letter is not an l, but a Ł, which is pronounced like a w – hence Łódź sounds like ‘wudzh’. Click here for a more accurate pronunciation.

Things To Do in Łódź

I really recommend Alex if you are looking for a guide to Łódź. You can contact her at aleksandra.ciach@gmail.com. For everything else in Łódź, visit the official tourism website.

All images taken by Mark Bibby Jackson (apart from the one he is in).