Roger Hermiston and Eileen Wise travel to Dublin and Cork inspired by James Joyce and other literary giants of Ireland.

It’s one o’clock on day two of our stay in Dublin, and quite unexpectedly we find ourselves squeezed onto a fading leather sofa in an oak-panelled room in the heart of Trinity College, one of the world’s oldest and finest universities. A murmur of anticipation flows through the audience packed into this small space, the majority of its students forty years our junior.

History seeps from every nook and cranny of this august institution as Irish literature’s finest have walked Trinity’s corridors – Swift, Goldsmith, Beckett, Wilde, and, more recently Sally Rooney. We were now about to be treated to a masterclass in storytelling from one of the country’s finest practitioners of the art.

A Talk at Trinity College Dublin

Joseph O’Connor, author (amongst so much else) of the wonderful bestselling historical novel Star of the Sea, had been invited to talk and read from his latest book, Shadowplay, a dazzling portrayal of the life of Bram Stoker, famed as the creator of Dracula but less well-known as the manager of London’s Lyceum Theatre in the late 19th century, and friend and confidant of the great actor Sir Henry Irving.

The event was hosted by Trinity’s ancient Philosophical Society (‘The Phil’), on the occasion of Stoker’s 175th birthday (there is also a thriving Bram Stoker Club at the college). We had stumbled across an advertisement for it the day before when visiting the college’s magnificent cathedral-like Old Library, with its great treasure the 9th century Book of Kells.

Gently prompted by ‘Phil’ president Ellen McKimm, O’Connor embarked on a spellbinding hour of anecdote, reflection and reading; rarely has an hour passed that was so stimulating and so enjoyable. At the end of it, after firing questions at him, he generously gifted us his own annotated copy of Shadowplay, and whetted our appetite with news of a new book, a World War Two thriller, to come in January.

The Westbury Dublin

More literary adventures were to follow, but first, we returned to our comfortable base The Westbury Hotel, only five minutes walk from Trinity and situated just back from Grafton Street, the city’s finest shopping thoroughfare.

The Westbury – which also pays homage to Dublin’s literary heritage with its splendid Wilde dining room – is one of the Doyle Collection’s stylish boutique city hotels. Its look is an attractive mixture of the classical and the grand (sweeping staircase, wide spacious public rooms) together with contemporary flourishes, especially the artwork.

Opened in 1984, it has energy and tranquillity in equal measures, a meeting place for locals in the heart of the city as well as a haven for its busy sightseeing guests. It certainly feels like the family-run establishment it is, with reception staff, concierges and waiters all exhibiting the ‘warmth and thoughtfulness’ that are the watchwords of Doyle hotel employees.

Our classic room (there are 205 suites and rooms) was on the fifth floor, equipped with sleep-inducing king-sized bed, luxurious armchair and sofa, and spacious bathroom complete with marbled floor and a powerful waterfall shower. On the large (55 inch) TV one breakfast time Roger was able to watch the England cricket team’s triumph in the T20 World Cup tournament in Australia.

Dining at Wilde Restaurant

A cocktail before dinner was just the tonic after miles of walking along Dublin’s compact city centre streets. The Westbury’s Sidecar Bar is straight out of the Roaring Twenties with its glitz and glamour, and a couple of traditionals (there are plenty more exotic) – a margarita and a Bellini – sent us into dinner at the Wilde restaurant suitably refreshed.

Wilde has a lovely covered garden terrace where we would take breakfast, but for dinner we settled down in the main, inside restaurant area, stylishly furnished and decorated with 1930s glamour. The food matched up to the elegant surroundings, Irish produce from local farms, river and sea – Lough rock oysters, Kilkeel scallops, Dublin Bay prawns and smoked salmon from Wrights of Marino – balanced with classic European cuisine. Top marks for the staff, too – our waiters were engaging, but also unobtrusive at the right moment.

Although we’ve travelled the length and breadth of Ireland, a stay in Dublin had somehow surprisingly eluded us. With just a couple of full days at our disposal, we decided to follow in the footsteps of the city’s literary giants, with Joseph O’Connor’s lecture being a marvellous, added bonus.

Museum of Literature Ireland

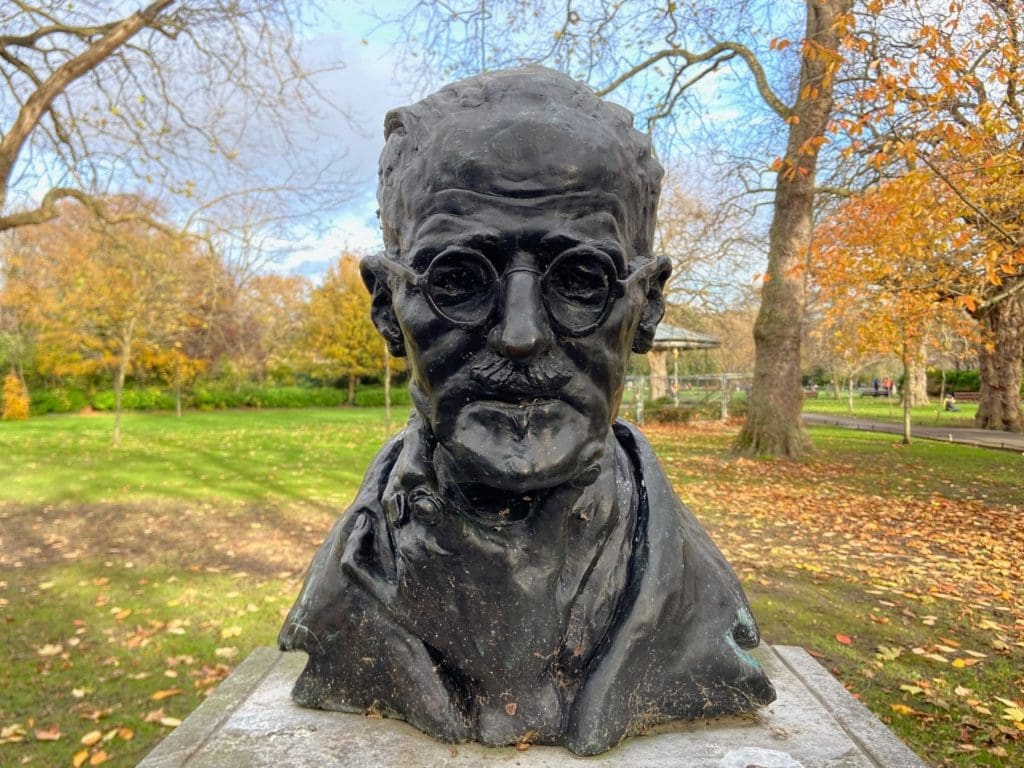

Remember this a city that boasts four Nobel Laureates in Literature – George Bernard Shaw, William Butler Yeats, Samuel Beckett and Seamus Heaney. Traces of all of them are scattered around Dublin, but of course no-one was more inspired by the sights, sounds and smells of the city than James Joyce.

It is 100 years since the publication of Joyce’s modernist classic Ulysses, the often stream of consciousness account of Leopold Bloom’s wanderings in Dublin on one day, 16 June 1904. We first picked up the Joycean trail in the excellent Museum of Literature Ireland (‘MOLI’ to all Dubliners) just off St Stephen’s Green, where we saw the very first edition of Ulysses, ‘Copy No 1’. An early draft of Finnegans Wake also resides here, as do numerous letters from James Joyce to publishers, friends and admirers.

The museum pays homage to the Irish storytelling heritage, has a room with quotes from the great poets and writers (together with audio recordings of some), and a final room where, suitably inspired, you can take a blank piece of paper and join hundreds of others in attempting to write the first lines of your debut novel.

But perhaps the most fascinating exhibit is a couple of pages of one of James Joyce’s notebooks for Ulysses, with three-quarters of the words crossed out by red, blue and green crayon, a veritable blizzard of editing. Confusion of thought, or meticulous in the extreme?

Following James Joyce

For the next Joyce landmark, a brisk walk down Grafton Street took us to a bridge over the River Liffey, bringing us to Dublin’s grandest boulevard, O’Connell Street, home to monuments and statues of Ireland’s great heroes. Just off it, on North Earl Street, a more than life-size brass statue of James Joyce, cane in hand, gazes loftily skywards. Perhaps the great man was getting too big for his boots – locals have dubbed it ‘The Prick with the Stick’, in the same irreverent way that Molly Malone’s statue on the other side of the river is referred to as ‘The Tart with the Cart’!

For our final Joycean experience we crossed back over the river and made our way to Sweny’s Pharmacy on Lincoln Place. In Chapter 5 of Ulysses (‘The Lotus Eaters’) Leopold Bloom stops at Sweny’s to buy some lotion for his wife Molly, and ‘waited by the counter, inhaling the keen reek of drugs, the dusty dry smell of sponges and loofahs’. He had forgotten the recipe for Molly’s face cream, but instead picked up a soap smelling of ‘sweet lemony wax’.

Sweny’s lemon-scented soap is a bestseller these days – no longer a pharmacy (since 2009), but instead a museum of sorts and the most authentic of all the Joyce venues. Run by nine or ten volunteers (with no public funding), it is presided over by charismatic language teacher P J Murphy, clad in a chemist-like coat with a black tie.

With the bell tinkling as you open the front door (‘Chemist’ and ‘Druggist’ are the signs that greet you above it), you are transported straight back to Victorian Dublin when Sweny’s first opened in 1847. Nothing much has changed since those days: the small shop features mirrored, dark wooded cabinets holding rows of colourful looking lotions and potions, and from a drawer P J brings out a few dusty brown-papered packages, unidentified prescriptions from decades ago (perhaps someone’s face cream?). Books, new and second-hand, are piled up on central tables, together with hats, face masks and t-shirts.

Enthusiasts gather in the evenings for readings from Ulysses, Finnegan’s Wake and The Dubliners – occasionally in different languages, once even in Turkish. This is an evocative, delightful place which has only served to enhance the Joyce legend in the last decade.

Easter Rising – Kilmainham Goal

If literature was our main theme for this Dublin visit, we also had to sink our teeth into the political event that for many defines Dublin – the Easter Rising of April 1916, launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland in the midst of the Great War.

There is much historical artefact to discover in the heart of the city about this famous armed insurrection – at the General Post Office on O’Connell Street, obliterated by British army fire, and St Stephens Green, a green haven today but dug up by the rebels into trenches then. But perhaps Kilmainham goal, a couple of miles out of the city centre, is the most haunting place associated with the Easter Rebellion.

Before 1916 it was the most important place of incarceration in Ireland. Something of a hellhole in the early years after it opened in 1796 – men, women and children huddled together in small cells – its conditions would improve after the great prison reformer John Howard visited and insisted on single cells and facilities for health and hygiene. Over the years Kilmainham was a barometer of political tension in Ireland and housed the most famous opponents of British rule.

Anthony, our extremely knowledgeable and articulate guide, delighted in showing us the most comfortable cell in Kilmainham – the one where Charles Stewart Parnell, leader of the Land League, ‘resided’ between October 1881 and May 1882. With a roaring log fire and an armchair, it was more a drawing room than a prison cell.

But the Easter Rising protagonists are at the heart of Kilmainham’s story. It was here that fourteen rebel leaders were brought to await execution after they had been summarily court-martialled and sentenced to death at Richmond Barracks. Anthony showed us the gaol chapel where the British, with a sliver of compassion, allowed one of them, Joseph Plunkett, to marry his sweetheart Grace Clifford the night before he was shot.

But it was Kilmainham Gaol’s Stonebreakers’ Yard that really caught the imagination. It was here between 3 and 12 May, in this grim place with its fearsome stone buttresses, that Plunkett and his thirteen colleagues were brought out, lined up against the far wall, and shot dead by a firing squad of 12 British soldiers.

However the last to be executed, James Connelly, died at the other end of the yard, next to the wooden gates. Unlike the others he had been in a military hospital, having been severely injured in the uprising. On 12 May an ambulance drew up outside the gates with Connolly in it, on a stretcher. He was levered out, propped against the wall, and his doctor asked if wanted to say a prayer for those who were about to shoot him. Connelly replied that he would pray for ‘All brave men who did their duty according to their own lights’. Connelly had himself been a soldier in the British army.

Much to reflect on after the Kilmainham visit. We did so at dinner on our final night in the city at an excellent vegetarian restaurant called Glas (Gaelic for green) just around the corner from The Westbury. It has a stylishly-designed art deco interior, with – as the name would suggest – plenty of leafy plants liberally distributed throughout. Delicious dishes of butterbean ceviche, and deeply flavoured roasted onion with charred halloumi and buckwheat, really hit the mark.

River Lee Hotel Cork

The next day we packed our bags and left The Westbury for Dublin’s Heuston station, where we boarded a train for a pleasant two-and-a-half hour journey to Ireland’s second city Cork. Our resting place for the next three nights would be another hotel from the Doyle Collection, the River Lee, only a few minutes walk from the city centre.

The River Lee Hotel is a stunning looking modern building with a great location on one of the bends of the eponymous waterway, cascading with light thanks to floor to ceiling windows throughout. It describes itself as ‘the modern face of Cork in the heart of the city’, but the site has a fascinating history too as it was the terminus of the famous Muskerry tramlines operating from 1880 to the 1920s, carrying passengers between North Cork and The City.

The view from our fifth floor deluxe king room was stupendous, out onto the slopes of the little hills beyond the River Lee where many of the city’s streets, public buildings and churches are situated. The room itself was extremely comfortable with a spacious sleek bathroom, restful armchair and luxurious bed. As a bonus, the latter also had an excellent reading lamp on either side, regrettably absent in so many hotels.

Leisure facilities mark out the River Lee, with a huge gym and – more importantly for us – a splendid 20-metre swimming pool, perfect for a rigorous thirty laps prior to a hearty breakfast (the Eggs Benedict is a treat).

We took dinner on our first night in the elegant Grill Room, where the food (especially the vegetarian offerings) and wine were excellent, matched by the service. On our final day, awaiting our departure to the airport, we spent some time reading in the library area of The Hub, the River Lee’s impressive floor (a mix of private rooms and open-plan area) for social and business events.

Cork International Film Festival

Cork is a vibrant place, a thriving cultural (it was European City of Culture in 2005) and gastronomic destination. For the latter, we duly made our pilgrimage to the world renowned English Market, here since 1788 and one of the oldest covered markets in Europe (called ‘English’ in the 19th century to distinguish it from another market close by named the ‘Irish’). What you find is exceptional locally produced artisan food, the counters brimming with exceptional cuts of meat and all manner of fresh fish, as well as herbs and spices, fruits and vegetables, sauces and oils, chocolates and cakes.

However as film buffs the real treat of our stay in Cork was to attend the city’s International Film Festival. It’s been running since 1956, and old timers told us that in its early days it used to attract big Hollywood stars to its premieres. It still has a varied programme of fresh drama and documentaries from around the world, shown at the historic Everyman theatre and the more modern Gate cinema.

We enjoyed three very different screenings – Armageddon Time, an absorbing rites of passage movie starring Anthony Hopkins, The Girl Can’t Help It, the 1956 classic featuring Jayne Mansfield, and a darkly delicious comedy/horror film, The Menu, with Ralph Fiennes playing a sinister chef.

Secret Destination Supper

The film organisers had a trick up their sleeve for the latter film. In keeping with the theme of the movie, they had organised a Secret Destination Supper. We managed to claim last-minute places, so we clambered aboard a coach at the end of the screening with about 30 others to be whisked away to our venue – some of us perhaps slightly apprehensive about what was to come, given the macabre content of the film we had just seen.

We needn’t have worried. It was to prove to be a simple modern diner a ten-minute drive away, where we were served burgers (inevitably from O’Mahony’s Butchers in The English Market). Now the beef burger is a key part of the plot in The Menu, the eating of which has dramatic, not to say bloody, consequences. Thankfully all was calm and we enjoyed a convivial couple of hours with fellow cinemagoers.

Less calm was our flight back to Stansted the following day, the plane being forced to land on ‘autopilot’ because of the dense fog. But it had been an invigorating and enriching week in the land of literary giants.

Doyle Collection Hotels

For more information on the hotels where Roger and Eileen stayed, visit: www.doylecollection.com.

Main image: Statue of James Joyce in Phoenix Park, photo by Mark Bibby Jackson