Before the pandemic, critics of Airbnb and overtourism argued that the two were inextricably interlinked and were changing the nature of popular neighbourhoods. Pauline Ronnet ponders whether Covid will change anything.

Thanks to greater global prosperity and broad technological advances, travelling for pleasure had never been easier pre-pandemic. Over the last decade, bigger, more efficient jets at budget airlines and bigger cruise ships had crammed passengers together and delivered them in ever-larger numbers to their common destinations.

Online booking, review apps, ride-hailing and home-sharing services have enabled tourists to have a smoother and even a more authentic experience at every step of the way. You can practically find out where you’re going to stay, what your neighbourhood will look like and where you’ll eat dinner on the first day just by sitting on your sofa and scrolling on your laptop at home. But these and other factors have interacted to create an unsustainable growth of tourists visiting the same destinations across the globe, to the detriment of both tourists and local populations.

The online home-rental platform Airbnb arrived in 2008, fundamentally changing how people travel – tourists could live next door to locals, whilst locals could conveniently make an extra living on their empty properties. Founded as an “airbed and breakfast” business in the living room of former schoolmates Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia, Airbnb’s exponential success has since been blamed for encouraging overtourism and worsening its impacts.

The problems with Airbnb and Overtourism

In certain attractive neighbourhoods, the percentage of Airbnb housing units can be significant. Having your sleep disrupted by noisy parties, not being able to park your car or having a view spoilt by conspicuous-looking tourists taking selfies is the day-to-day cost that permanent residents have to pay for having been born or adopted into an exceptionally beautiful city.

Over time, high levels of tourism can lower a resident’s quality of life in a way that goes beyond daily annoyances, like changing the feel of the neighbourhood and eroding the sense of community within it as local businesses start catering to tourists.

A central issue with Airbnb is that people exploit its money-making potential by purposefully buying up empty properties and renting them out, relying on this practice as their main source of income.

Ultimately, this means that residents may be forced to leave their cities due to not being able to find lodging since it is far more lucrative for landlords to provide short-term rentals to tourists than long-term rentals to locals. A study has also pointed to a causal relationship between the percentage of Airbnb listings and increases in rent and house prices.

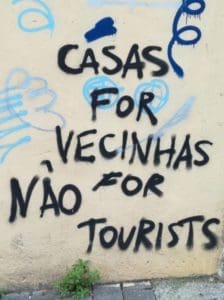

Airbnb and Overtourism: Houses for Neighbours, not for Tourists

Photo taken by me on a holiday to Porto, Portugal, in October 2019. The graffiti reads “houses for neighbours, not for tourists”. We stayed in an Airbnb flat. Just across the road was a restaurant bar selling fast food and obviously not a local hang-out. The main street was a luxury shopping avenue with flashy overpriced cafes lodged at intervals in-between shops. We bought a bottle of Porto wine in that avenue, it wasn’t bad but the cork crumbled to pieces when we opened the bottle and we had to drink wine with bits of cork. Porto is a beautiful city but is in many ways almost uninhabitable and un-visitable. A non-stop growth of tourism in this city has ultimately led to an unfulfilling tourist experience and livelihoods dominated by the tourism industry.

The future of home-sharing

With most people now stuck at home, Airbnb bookings have collapsed. A study published in 2020 predicts that the economic super-shock delivered by Covid-19 means that bookings will never return to pre-pandemic levels. It also typifies hosts according to their approach to home-sharing.

Hosts that have mortgages on their properties and earn their livelihood through short-term Airbnb rentals (termed ‘capitalist’ hosts) have been hit hardest by the recession and many have transitioned to long-term rentals. Hosts motivated by less commercial interests and who used Airbnb to actually share their homes – as the platform was originally conceived for- were less impacted. Could this signal a permanent return to Airbnb’s original home-sharing ethos? The authors would argue yes, because the dramatic and global nature of the economic shock has permanently changed how often people will travel.

Read Pauline’s view on the Future of Travel and Tourism in Venice.

Another study published in December concluded that the pandemic does provide an opportunity for a transformation of the tourism industry into a more sustainable model if the right policies are employed. This could lead to a decline in the numbers of ‘capitalist’ multihosts and more of the alternate types who are in it to socialise with their guests or are guided by ethical principles around sharing space.