Mark Bibby Jackson looks into how the aviation industry can reduce its CO2 emissions.

My favourite Disney film of all time is Dumbo. As a child, I loved to see that little elephant unfurl his ears and slowly take to the air. If only flying could be that simple – and clean.

Nowadays, there is another flying elephant – the aviation industry itself. Time and again in discussions on how to clean up the travel industry’s carbon emissions, aviation is referred to as the ‘elephant in the room’. And it is easy to see why.

Aviation CO2 emissions

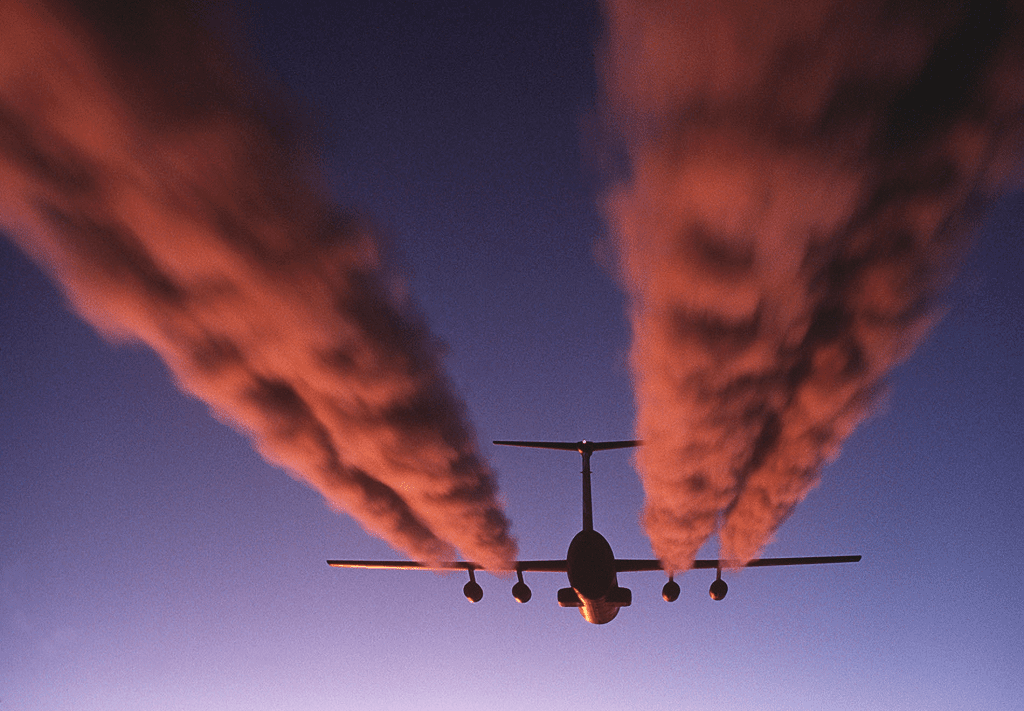

Aviation contributed 915 million tonnes of CO2 emissions in 2019. This is estimated to be some 3% of global CO2 emissions. And it is growing – at least it was pre-Covid.

Although the industry has been cleaning its act up, with a reduction in CO2 emissions per kilometre of just over 50% since 1990, the total emissions continue to rise due to the increasing number of flights made each year. In 2019 there were 46.8 million scheduled flights carrying 4.5 billion people.

Yet it is only a small proportion of the world that flies each year – an estimated 11% of the global population in 2018, while 1% created half of aviation’s carbon emissions.

CORSIA or Hot Air?

The airline industry has taken measures to regulate its CO2 emissions – not only in fuel efficiency which it could be argued is driven by economic motives.

In 2016, the ICAO Assembly adopted CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation), which is due to expire in 2035, and at least in its current form not designed to reduce any emissions.

Some within the industry, describe offsets as a ‘get out of jail’ card, akin to paying someone else to give up smoking for you

Instead the agreement stipulates that 80% of any increase in CO2 emissions subsequent to 2020 should be offset. This base figure was later changed to 2019 due to the significant drop in air traffic in 2020 due to Covid, which would have made this target even more difficult to achieve.

Some within the industry, describe offsets as a ‘get out of jail’ card, akin to paying someone else to give up smoking for you.

The aviation industry’s aim is to reduce its 2050 CO2 emissions to half the 2005 level in order to align with the Paris Agreement targets.

To achieve this there needs to be a significant shift in the way that the industry is run and regulated.

There is no magic vaccine to fix the problem of international aviation’s CO2 emissions

No Vaccine for Aviation Industry

There is no magic vaccine to fix the problem of international aviation’s CO2 emissions, but rather a menu of options that taken together can help reduce the industry’s toxicity.

While technology is constantly evolving and reducing CO2 emissions caused by airplanes, inevitably there is a time lag between envisioning and implementation.

Last year Airbus stated it was developing prototypes for hydrogen zero emission planes it hopes will come into operation by 2035. Boeing has just announced plans to produce planes that can fly on 100% biofuel by 2030.

What happens in the meantime?

Some argue that biofuels, or sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) represent the future. But even optimistic industry estimates calculate that these would lead to a reduction of CO2 emissions by 2025 of some 5 million tonnes, or approximately 0.5% of the total aviation CO2 emissions generated in 2019, although this could change with innovation in what is a highly technologically driven sector.

Clearly, there are major efficiencies that can be made in the way international aviation is managed. For instance, air traffic control alterations so that planes adopt the shortest flying route, a reduction in taxiing time and more gradual altitude changes in take offs and landings would all reduce CO2 emissions.

All these measures will help, but alone they seem insufficient if the industry wishes still to grow, yet to reduce its real emissions – not next emissions including offsets – by 2050.

A Golden Bullet

For many the Hydrogen plane is the golden bullet, but as mentioned earlier this is not likely to happen in the next 15 years or so. Then, at least according to initial designs, planes will only be able to fly on short routes (under 1,000 km), which are not the real problem. Some 80% of CO2 emissions stem from flights of more than 1,500km.

The next decade needs to see a seismic shift in the way that the aviation industry deals with its carbon emissions

Even if technology improves sufficiently to allow hydrogen powered planes to operate on long haul flights, this still begs the question about what happens in the interim 15 years. This is vital if aviation, just like every other sector, is to meet the Paris Agreement targets. For many, regard the next decade as crucial to achieving this. Procrastinate much longer and it will be too late.

A Systemic Change

The next decade needs to see a seismic shift in the way that the aviation industry deals with its carbon emissions.

Some advocate a carbon tax. But surely any money thus accrued will soon become lost in various governments’ treasuries. How will it actually redress the main problem of increased carbon emissions? To deter people from flying sufficiently to tackle the CO2 problem, any carbon tax would have to be substantial. Is this what either the aviation industry or passengers wants?

Carbon offsets could be part of the solution, if they are real offsets that help to preserve the planet’s biodiversity, but by definition these are offsets rather than reductions.

No Fly or Fly Better?

This leaves us with the thorny question as to whether the aviation industry should grow at all?

Aviation advocates point out to the multiple benefits that a robust aviation sector brings with it. And amongst the many lessons of the past year we can count how business suffers when aviation is paralysed.

There is a growing case that domestic and pan-continental travel could be diverted from air to rail

Anti-flight campaigners such as the No Fly Movement advocate that people should reconsider whether they fly as a matter of principle.

Certainly, there is a growing case that domestic and pan-continental travel could be diverted from air to rail, or perhaps to electrified vehicles. But there again investment in rail infrastructure is a long and fraught process not without its environmental critics, as the UK’s HS2 project demonstrates. As for electric vehicles, including trains, we have to consider how green the energy power source is – if the electricity comes from coal burning is it really any greener than a plane?

Taking all the above into account, it is hardly surprising there are so many different views on how the aviation industry should be decarbonised – if indeed it should.

The Solution – the Space to Breath?

Hopefully, power to liquid and hydrogen power can provide the answers. In the meantime, a mix of sustainable aviation fuels, genuine biodiversity–orientated offsets, investment of existing tax benefits in developing more sustainable fuels, greater efficiencies in air traffic management and operations, and a transfer of domestic and short haul travel from air to rail could provide us with the breathing space to develop the necessary new technologies.

Just like Dumbo perhaps we need to take a leap of faith and ignore all those people laughing at us

If that sounds like a complex solution to a simple question, just remember that it took centuries for man to learn to fly.

Professor Geoffrey Lipman, President SUNx Strong Universal Network, has recently invited Jeff Bezos and Jack Ma to match Elon Musk’s recent $100 million carbon capture award, and launch a similar award for the best ideas to accelerate zero carbon flying. Could this lead to the answer we are all seeking?

Just like Dumbo perhaps we need to take a leap of faith and ignore all those people laughing at us. The answer can be achievable so long as we do not ignore the elephant in the room. For one thing is for sure we do not have much time to fix the problem if we are to achieve our Paris 2050 target.