After crisscrossing Bangladesh by boat and bus, Johan Smits concludes his Bengal travel saga in Cox’s Bazar and gets away from it all on the longest beach in the world.

Where on our crowded planet can you still walk long, uninterrupted hours along deserted beaches? No overtourism, no concrete buildings degrading the landscape and no washed-up heaps of rubbish. Just vistas of seemingly unending beach and sea. And if such a place exists, then why does it not feature prominently on the international tourist map? I found the answers to my questions somewhere along the Bay of Bengal in Bangladesh, close to the border with Myanmar.

Longest beach in the world

I happen to prefer mountains over seascapes, but my two-hour solitary walk along the beach of Cox’s Bazar, a port city in Bangladesh, confirms there’s always an exception that proves the rule. It’s vast, varied and blessed with a raw, natural beauty.

The sun is already preparing itself for a dip into the Indian Ocean as I watch a lone fisherman braving the surf to cast his nets. Thanks to the low tide and the seabed’s gentle slope, he’s wading far into the waters. Completing the picture is an ominous dark yellow sky that turns all into a dramatic scene of man against the elements.

Earlier on I passed by a tiny fishermen’s commune with a number of eye-catching fishing vessels lined up on the sand. Curved keels and high bows and sterns give them an intriguing half-moon shape. These so-called moon boats are made by local Bengal carpenters using generations-old techniques. The sight of their dark, half-moon profiles set against the open sea is mesmerising, but here on the beach I admire their elegance and craftsmanship from up close.

Consisting of a whopping 125 kilometres of tropical sands, Cox’s Bazar’s is the longest beach in the world that is natural and uninterrupted. It’s taking ‘a stroll up and down the beach’ to another level – it would keep me busy walking for a week. There are different names for distinct sections of this long expanse. Himchari and Inani beaches are amongst the more familiar ones, located respectively eight and 23 kilometres south from Cox’s Bazar’s tourist centre. It’s along these more secluded parts I prefer to take my walks.

Despite its natural coastal beauty, Cox’s Bazar is not the tropical paradise you find in brochures. Huge sandbags and long stretches of conifer plantations protect the coast against surging tides, while the waters here come in shades of grey and blue, rather than turquoise. Yet, what really sets Cox’s Bazar apart is its hosting of the world’s largest refugee population.

When at the end of 2017 hundreds of thousands of Rohingyas fled state-inflicted violence and genocide in Myanmar’s Rakhine State, they ended up just across the border in Cox’s Bazar. Here they joined Rohingya refugees from previous persecutions who are surviving in cramped conditions in camps that now shelter nearly a million of them. As a consequence, an army of local and international aid workers is now also very much part of the present landscape of Cox’s Bazar.

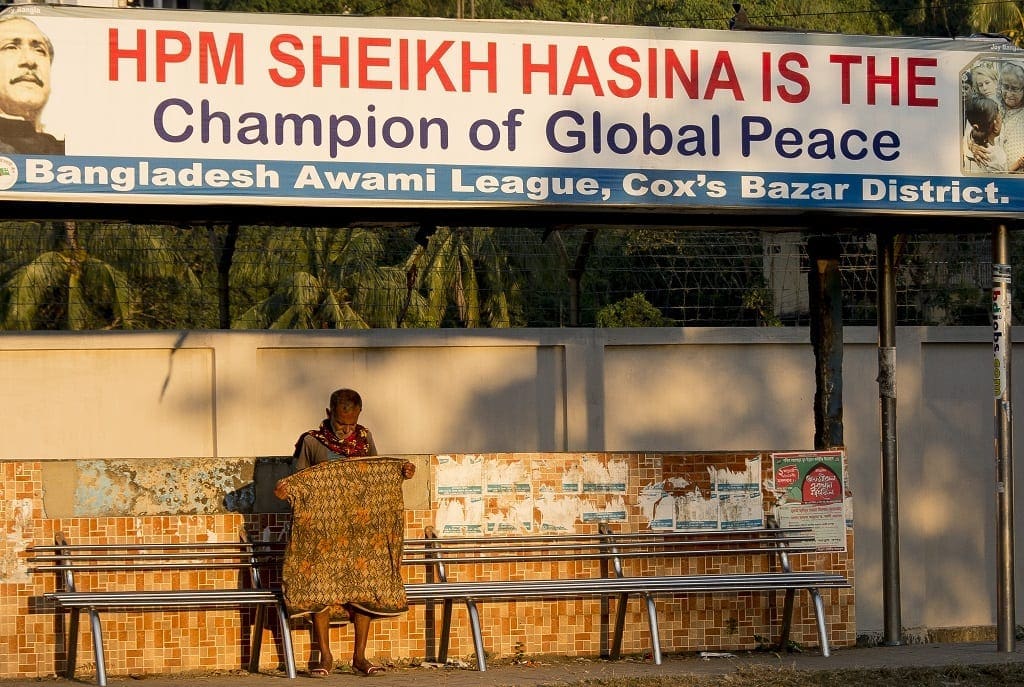

Cox’s Bazar beachfront

The presence of international relief workers who hail from Africa to Europe and from the Middle East to the Americas; of photo journalists and TV crews sent by global broadcasters; of excited middle-class Bangladeshi holidaymakers clad in colourful hats and cheap sunglasses; and of a deeply impoverished segment of local residents surviving in shanties next to four-star hotels – all of this makes for a cocktail of hugely different worlds convening in a few blocks in Cox’s Bazar’s beachfront called the hotel-motel zone. It’s a strange micro-cosmos of humanity you would normally never expect at a beach resort.

When I explore this hotel-motel zone, my revulsion is held at bay only by an admittedly dubious kind of fascination. I witness holidaymakers preparing food in the middle of rubbish dumps. Children are playing around wide open sewers while their parents have dinner on wooden boards that only partly cover the cesspools underneath. I can hardly believe the medieval scenes of rubbish dumped from multi-storey buildings onto the streets below. Toxic wafts of burning waste greet me at every other street corner. Amongst all this, cows, goats and chickens roam the dirt roads feeding on plastic and other refuse until they themselves end up on dinner plates. Meanwhile an uncontrolled construction orgy of badly planned apartment blocks and hotels – some remaining unfinished – has turned the area into an asthma danger zone.

It’s not the first time I’ve encountered these scenes during my Bangladesh travel, but never in such intensity. It is heartbreaking, especially as I recall the warm Bangladeshi friendliness and non-judgmental hospitality I have been shown throughtout my stay – in particular from ordinary people such as rickshaw drivers or street vendors.

Every high season (October to March), hundreds of thousands of holidaymakers from all over the country descend here, making it Bangladesh’s top tourist destination. Cox’s Bazar City, with a population of only 250,000, has the capacity to host over 85,000 daily visitors in accommodation ranging from cheap budget motels to five-star hotels, mostly concentrated in a few blocks in the hotel-motel zone.

Yet, the vast majority of this crowd remains concentrated on Cox’s Bazar’s most popular beach called Labonee.

This being a fairly conservative society, I’m not surprised by the absense of bikinis or speedos on Labonee Beach – even when out swimming people are fully covered. What does surprise me is the presence of a small but burgeoning surfing scene led by a modest surfing school called Surfing Bangladesh. Even more surprising, more than half of the surfers are girls.

With child marriage and child labour still prevalent in Bangladesh, Cox’s Bazar’s little surfing school is offering these young girls and boys some respite. Cox’s Bazar’s surfing girls have even become the subject of a recent documentary called Bangla Surf Girls which is currently doing the competition circuit of international film festivals.

The public expectation of dressing conservatively while out on the beach is not the only barrier that may discourage foreign visitors from choosing Cox’s Bazar for a beach holiday. Bangladesh is a dry country which means I can only have a beer in a couple of overpriced and rather gloomy hotel bars. This only further increases the unlikelihood that this resort town will make it onto the international tourist map any time soon.

When I’m out on Labonee Beach I find I’m often the only westerner around and this unfailingly results in a ridiculous number of selfie requests – some of them pretty insistent. I never thought I would empathise with Hollywood royalty venturing into public life, but if your ego needs a bit of a boost then this is the place to hang out.

The concentration of the crowds on Labonee Beach means there’s plenty of space for beautiful, solitary beach walks on mostly deserted stretches elsewhere. While the general lack of tourist facilities at the more remote parts of Cox’s Bazar’s endless beach means you have to put a bit of planning into your excursions, this is more than compensated for by the vast, pristine seascapes to enjoy. Something increasingly rare in the world.

Cox’s Bazar City and beyond

Although Cox’s Bazar’s main drawing point is incontestably its huge beach, I’m also drawn to exploring its historical centre and further afield. The busy streets I find here are flooded with colour and an amalgamation of different noises – from honking motorcycles and yelling street traders to crackling public loudspeakers broadcasting the azan and official announcements. As such, Cox’s Bazar’s commercial centre feels to me very similar to those of other cities and towns I’ve visited in Bangladesh.

First established in 1854 as a market or bazaar, Cox’s Bazar was named after the Scottish captain Hiram Cox who was a superintendent of the British East India Company. Cox was stationed in what was then called Palongkee and did a lot of work on the rehabilitation of Arakan refugees who were fleeing Burma’s armies that had invaded Arakan, or present-day’s Rakhine State in Myanmar. It was a foreshadowing of the Rohingyas’ current plight, it now seems.

Given the city’s location at the coast, I’m not surprised when I end up at a busy fishing port at the Bakkhali River. It’s afternoon and the activity here is more thriving than frenzied now. Wooden fishing trawlers are sailing up and down the river, local sellers show off their catch of the day, and big blocks of ice are cut up to keep the fish fresh for transport. Many are for export to places like Dubai, one of the traders confides in me, while the lesser quality fish end up on the local market.

Cox’s Bazar is also home to a number of Buddhist sites, not unlike the ones I saw in Rangamati in the Chittagong Hill Tracts further north along the Myanmar border. One of the highlights is a statue of a reclining Buddha in the village of Ramu, about 10 kilometres from Cox’s Bazar. At 30 metres in length, it’s said to be South Asia’s largest reclining Buddha.

Easier to visit, a little hidden away but right in the centre of town, is the Aggameda Khyang. It’s a 19th-century Buddhist monastery of which its main sanctuary stands elevated on timber columns. The abbot shows me several bronze Burmese Buddha statues – some of them a couple of hundred years old he tells me – as well as a few important manuscripts.

While these places in themselves are interesting enough to stray away from the beach, it’s more the general ambience that leaves an impression on me. Unlike in Rangamati, the Buddhist community in Cox’s Bazar constitutes only a tiny minority of half a percent of the local population. I cannot help but feel that there is a worry about the effects of Myanmar’s persecution of Muslims on the Buddhist minority here in Bangladesh. Or to say it with the words of the abbot, “we have dark times”.

It’s not that long ago, at the end of 2012, that a mob of hundreds of people rampaged through Ramu and destroyed a number of Buddhist temples, houses and many religious artefacts – an event that must still be haunting people’s memories. Yet, given the scale of the violence across the border, the fact that no retributive incidents have happened here in Cox’s Bazar seems testimony to the efforts of the local government and communities to protect the peace.

Is Cox’s Bazar then, at least to some extent, a compressed reflection of the state of our fragile world? A living symbol of the immense pressure we exert on our planet’s environment, of the displacement of entire populations, and of the stark juxtaposition of poverty and affluence – but with this community’s acceptance of nearly a million refugees, perhaps also of a certain resilience and hope? After crisscrossing this incredible country, from its capital Dhaka to the Sundarbans mangrove forest, and from the Chittagong Hill Tracts to its beautiful coast, I’m looking forward to having a last walk before I bid goodbye to it all. There’s a lot to reflect on, but then, it is the longest beach in the world.

Cox’s Bazar and the longest beach in the world: photo gallery

Cox’s Bazar hotels and when to visit

During high season, from October to March, prices become inflated and Labonee Beach crowded, especially in December and January. However, the weather is most pleasant then and even during this period you will find beaches further away deserted. Other parts of the year are quiet even on Labonee Beach, but note that June to September is the rainy season and cyclones are possible from March through July and September through December – yet always with plenty of advance warning.

There is plenty of accommodation in the hotel-motel zone of various standards and prices. However, if you want to stay somewhere more secluded then Mermaid Beach Resort and Mermaid Eco Resort are relatively pricey but very comfortable and recommended. They are located on Marine Drive along the longest beach in the world, respectively 14 and 15 km from the tourist zone, and can be reached by tum tum or CNG (auto-rickshaw) within 25 minutes.

There is plenty of accommodation in the hotel-motel zone of various standards and prices. However, if you want to stay somewhere more secluded then Mermaid Beach Resort and Mermaid Eco Resort are relatively pricey but very comfortable and recommended. They are located on Marine Drive along the longest beach in the world, respectively 14 and 15 km from the tourist zone, and can be reached by tum tum or CNG (auto-rickshaw) within 25 minutes.

I really enjoyed reading this post. Do I even need to visit it myself now..

glad you enjoyed the post