In the fictional Neverland the inhabitants either don’t age – or in Peter Pan’s case, refuse to grow up. Could a newly-rediscovered remote island in the Mergui Archipelago, Myanmar be a real-life Neverland? Keith Lyons investigates.

It has been dubbed ‘the last island frontier’, one of the final island paradises left on Earth, and chances are, you’ve never heard of the scattering of 800 islands off the coast of Myanmar and Thailand. For much of the 20th century, the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea was off-limits to all, and apart from some sea-faring nomadic Moken and illegal poachers, the island group was largely uninhabited.

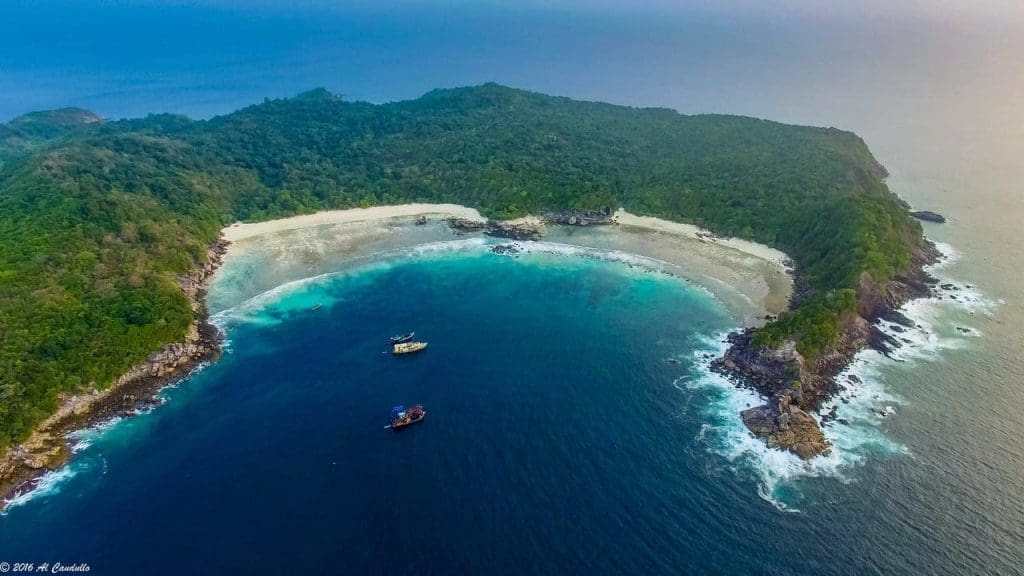

Stretching more than 400km north to south, and covering an area larger than Belgium, Israel or Taiwan, the archipelago straddles the Thai-Myanmar border, with limestone and granite islands and rocky atolls covered in tropical forest, fringed with white-sand beaches and coral reefs.

A History of Exploitation

In keeping with its past ‘pirate-infested’ history, for half a century the archipelago proved to be the ideal location for exploitative extractive industries, from mining and logging to fishing, with a clandestine smuggling economy in cahoots with the Burmese junta which controlled the country from 1962 up until 2011. Unregulated trawling, long-long fishing, and night-light fishing have depleted fish stocks and reduced larger species such as sharks and rays, with the most damage from dynamite fishing, which has left behind tell-tale rings in the coral reefs.

“The Mergui Archipelago really is one of the few untouched places left”

The Burmese military government only allowed limited access to foreign charter live-aboard boats to dive among sharks and rays at the Burma Banks sea-mounts and western outer islands since the late 1990s. Venturing into the islands from Thailand’s Phuket or Ranong for diving or sport fishing was prohibitively expensive, and even today royalty fees can be over $250 a person, to be paid in new US dollar bills, for the rare opportunity to dive at Black Rock or Shark Cave with silver, white, black-tip, nurse, tiger and hammerhead sharks.

It is only in the last couple of years that adventurous travellers have been allowed to actually stay overnight on any of the islands, with only a handful of islands permitted to be developed for small-scale, sustainable tourism.

Sustainable Eco-tourism in the Mergui Archipelago

“The Mergui Archipelago really is one of the few untouched places left,” says Norwegian Bjorn Burchard, a pioneer in the region. “Much of the archipelago is still unexplored. Some of the islands have never been set foot on. Few people know about the place. And because of the challenges of access, few people visit.”

He likens the islands to what Thailand was like three decades ago, and believes there’s potential for sensible, sustainable eco-tourism through boat-based island-hopping safaris and small-scale island-bound tourism.

“There is an opportunity here, but also a danger that without proper guidelines and management it quickly becomes spoilt like Phuket,” he says.

“I’ve worked on similarly sized reefs that only have about a third of the coral diversity that we see here on Boulder Island”

Endeavouring to demonstrate the long-term value of tourism overfishing, and how marine-tourism can benefit not just visitors but also local fish stocks, Boulder Bay Eco-Resort is supporting marine conservation efforts around one of the archipelago’s most diverse outer islands. As well as striving to have a minimal footprint on the land, staff have been combing the island’s four beaches collecting plastic and rubbish. Not all is shipped back to Kawthaung for re-use, recycling and safe disposal, as some is used for making eco-building products. Discarded fishing equipment washed up on Boulder Island is being re-purposed as building blocks for an innovative coral reef restoration trial.

Environment First in the Mergui Archipelago

Working with Project Manaia, the Association for Ocean Conservation, more is being discovered about the island’s reefs to share not just with visitors but to help preserve the unique coral gardens and fish-life. Now in its fourth year, the initiative has revealed a rich diversity in five bays around the island, and healthy coral and fish populations.

“I’ve worked on similarly sized reefs that only have about a third of the coral diversity that we see here on Boulder Island,” says American marine biologist Thor Jensen who completed an island reef survey with German Annika Dose. The pair successfully trialled using locally-found materials for reef restoration, removing traps from washed-up fish cages to form new habitat for both coral and fish.

A future Project Manaia programme will study the clownfish (as featured in the movie Finding Nemo), which lives symbiotically among sea anemones. There is a push to create the first no-take marine zone, to enable the replenishment of species including the iconic clownfish, sea turtles, moray eels, stingrays and sharks.

Most of the resorts which have opened in the archipelago have a strong environmental ethic

With limited Wifi, no phone signal, no shops, no nightclubs, no ATMs, no air-con, and no bars, Boulder Island Eco-Resort offers a digital detox, and an opportunity to be rejuvenated by an intimate connection with raw wilderness. Beach bungalows nestled behind palm trees allow vistas of the bay of white soft sand flanked by rounded limestone boulders. Hermit crabs make their way along narrow jungle paths, crickets sing above the white noise of the waves, and fireflies dance around on the cool sea breezes.

Most of the resorts which have opened in the archipelago have a strong environmental ethic and are required to adhere to strict environmental safeguards, including not cutting down trees, using local spring water, reef-safe products, and biodegradable soaps.

At Awei Pila, there has been a drive to reduce all plastics, and staff have been involved in beach clean-ups and removing ghost nets and debris from the sea. Nearby, Wa Ale Resort inside the Lampi Marine National Park, protects turtle nest sites on its main beach, and a percentage of revenue goes towards conservation, healthcare and education projects. A coral planting programme at Nyaung oo Phee Resort is part of the effort to preserve the half dozen diverse snorkelling and dive sites around the island.

“The moment I saw the map I was struck at how closely it resembled Boulder Island”

The islands are suited to soft adventure activities and slow exploration, with Moby Dick Tours offering island-hopping trips aboard the old converted junk MV Sea Gipsy, which stops at sheltered bays and off sandy spits to allow guests to swim, snorkel, or kayak in the warm, crystal-clear waters. One of the rest stops is at the ‘115’ island group – some of the islands haven’t been named, and some beaches have never been set foot on.

Only a few hundred foreign visitors explore the islands each year during the season October to May (outside the monsoon season), and while the archipelago is regarded as relatively pristine, and certainly free of the tourist crowds which flock to Thailand’s islands, there’s a new claim that the location might have fuelled the creation of an island known to most children around the world.

Is Boulder Island Neverland?

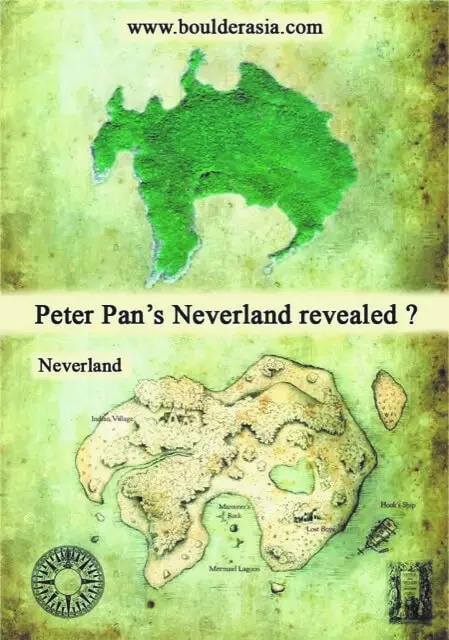

Boulder Island might have provided inspiration for the J M Barrie’s Neverland. A quest to verify whether the fictional world had a real-world inspiration was triggered when a satellite photograph of Boulder Island proved strikingly identical to an antique-style map of Neverland found on eBay.“The moment I saw the map I was struck at how closely it resembled Boulder Island,” says Burchard. “It was amazing how similar they looked, with the same features of beaches, bays, coastline, jungle, lakes, islets and rocks.”

Former Indian Army cartographer and surveyor, Col Sanjay Mohan, of Map & Locations, who has examined maps of the fictional island and satellite images of Boulder Island, says the puzzle of Neverland’s location and origins reveals much about the role of the imagination and stories in map creation.

“The resemblance of a real island in the Andaman Sea to Peter Pan’s Neverland could just be a coincidence, or it could be because the map-maker took inspiration from the actual map or chart of Boulder island,” he says.

A Literary Inspiration?

An intriguing set of coincidences and links, confirmed by historians, cartographers, literary experts and authors, has speculated that the Scottish author JM Barrie knew of Boulder Island when he conjured up the fictional world of Neverland more than a hundred years ago. He never visited himself, but there are many ways in which his imagination was fed by what he read, saw and heard, including travel narratives, colonial memoirs, and boys’ adventure stories, including Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island.

The island and surrounds featured many of the characters found in the Peter Pan adventures

Barrie was planning to visit Stevenson, but the Treasure Island author died before he could make the voyage. Many of his friends and contemporaries had lived in or visited Burma, including poet Rudyard Kipling who probably sailed past the island.

While the claim is new, even a century ago writers such as Major C.M. Enriquez in Burmese Wonderland (1922) likened Burma to a real-life Neverland. Other evidence indicated that the island and surrounds featured many of the characters found in the Peter Pan adventures, including pirates, crocodiles, Indians (ethnic nomadic sea-gypsies), and even mermaids (dugongs or manatees mistaken for sirens of the sea).

The Neverland pirates aboard the Jolly Roger – Captain Hook and his henchmen – have their origins in the stories of real-life robbers of the high seas, dating back to the golden age of piracy between 1650 and 1720, says researcher and novelist MF Webb, whose six-year investigation is outlined at Hook’s Waltz. Pirates were notorious in the Andaman Sea and the Indian Ocean.

One of the strongest connections is that Boulder island was originally named in the 19th century by the famous Scottish hydrographer James Horsburgh, whom Barrie would have learnt about at school. Barrie was not just fascinated about islands, but also shipwrecks, with one of his first plays (The Admirable Crichton) about a group of shipwrecked men. He was asked to pen the introduction to a later edition of The Coral Island, writer by another Scotsman, R.M. Ballantyne, where he wrote, “To be born is to be wrecked on an island.”

Interestingly, Horsburgh was shipwrecked in the Indian Ocean, this event driving him to create better maps and charts of the region. Horsburgh Island, with its distinctive shape, features prominently on early nautical charts and maps due to its location in the outer edge of the treacherous coral island archipelago.

“Barrie would have been familiar with Horsburgh’s achievements for the East India Company, and in creating an island, perhaps he used the island surveyed and named by the hydrographer for his inspiration,” says Burchard.

Left to the Imagination

During the British colonial times, the Mergui Archipelago served as a carefree holiday destination for Brits posted to Burma, paralleling the role of Neverland as a place of eternal childhood, escapism and immortality. In Barrie’s plays and stories, islands were often used as the setting to emphasise it being a ‘lost place’.

“All our experiences feed into our imagination,” says Peter Glanville, CEO and Artistic Director of the Polka Theatre in London, which won an Off West End Award for its Peter Pan production in 2015. “Peter Pan is littered with references that are from J.M. Barrie’s life so the idea of an actual Neverland as inspiration isn’t a problematic one,” he says.

While Neverland is a made-up fictional place, Glanville says that on a personal level, fictional worlds inhabit our minds alongside the real, all mashed up together. “The idea of a place where we never grow old, freezing time, is a useful device for exploring our mortality and our humanity.”

The Mergui Archipelago’s long reputation for menacing pirates and its roaming sea gypsies certainly add to the case for Boulder Island being the inspiration for Neverland, says travel writer Christopher Winnan, author of Around the World in Eighty Documentaries.

“Very little is known about the remote islands of the Mergui Archipelago, so who is to say that Boulder Island itself might not be inhabited by even more unusual inhabitants? Tinkerbell and the Lost Boys may not frolic among the hollow tree trunks, but clownfish and parrotfish still play hide and seek in the coral reefs.”

Getting to the Mergui Archipelago

The requirements for a Myanmar visa, and the set weekday departures of boat transfers to the private resorts such as Boulder Island Eco-Resort, as well as seasonal nature of the location – October to May – mean some planning and preparation is required to get to Neverland.

Best access is through Ranong in Thailand, connected to Bangkok’s budget airport Don Mueang with regular flights, or five to six hours away by car from the hub airport of Phuket. From Ranong’s port, after immigration formalities are completed, it is a short long tail boat journey across a wide river estuary to the southern-most tip of Myanmar, Kawthaung, where e-visas are stamped. There are also daily flights to Kawthaung from Yangon, for those already in Myanmar.

The lack of direct flights, as well as the long boat transfers, means travel times are long, but the journey to your own tropical island getaway is worth it.

Photos: David van Driessche (www.davidvandriessche.com).