Mark Bibby Jackson journeys to the city of Lichfield where he visits the cathedral, Samuel Johnson’s birthplace and the nearby National Memorial Arboretum, before departing in sombre mood.

A sense of déjà vu sweeps over me as I clamber my way up the narrow stairs leading to the roof of Lichfield Cathedral. Was it not only the previous year that I had undertaken a similar feat at nearby Derby Cathedral? It was becoming a habit. In any case, this was good practice for my forthcoming hike in the Swiss Jungfrau, I convinced my reluctant legs.

Whereas at Derby, the sole purpose of the climb was to view the city, at Lichfield there is a more internal purport to my ascent.

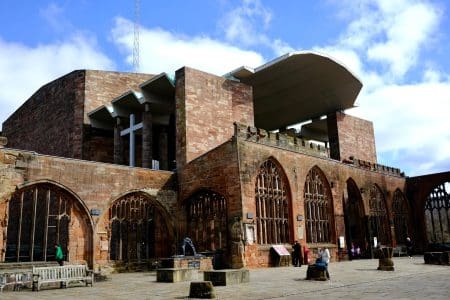

Lichfield Cathedral

The first cathedral was built on this site around 700, with the current third cathedral dating from 1190. One of the smaller cathedrals in England, Lichfield is notable for being the only medieval cathedral with three spires, the main one being added in the 14th Century. Lichfield Cathedral was particularly damaged in the English Civil War. Surrounded by a thick wall, only part of which remains, the building was of strategic importance, as Roundheads and Cavaliers wrestled for its control.

A series of stabilisation works was carried out under the stewardship of James Wyatt in the 1790s, and it is around this – as much as the views of Lichfield itself – that the Hidden Heights Tour takes me.

From within the cathedral’s rafters you can see the solid oak that was donated by Charles II, as well as the plaster Wyatt used to replace the previous stone vaulting to reduce its weight. Down below within the cathedral you can see how the columns supporting the vault had bowed. Up here it’s noticeable how Wyatt reduced the dimensions of the roof to further reduce its load-bearing burden. It must have been a considerable feat of engineering.

Erasmus Darwin House and Samuel Johnson Birthplace Museum

That is not to say that the view from the cathedral’s roof is not spectacular. From it you can see most of the city pretty much as it was laid out by Roger de Clinton between 1130 and 1150.

It is to the city of Lichfield that I head next. First, we stop off at the house of Erasmus Darwin, where the grandfather of Charles moved to in 1758. Its pleasant gardens in truth outweigh the simple exhibition inside, unless you are of a particularly scientific persuasion. However, it has the distinct benefit of being free of charge.

So too is the house where Samuel Johnson was born in 1709. Constructed for his mother and father from 1707 to 1708, the building has been converted into an impressive museum devoted to the life of the man most noted for his English Dictionary.

A copy of Johnson’s original lexicon published in 1755 is on display in the building’s attic. Though not the first in the English language, it is generally accepted that Johnson’s set the style for others to follow. You can peruse the great man’s now somewhat pompous definitions in a replica copy in the same room as the original.

Patience Rewarded at Swinfen Hall Lichfield

Prior to dinner, we check into our hotel, the luxurious Swinfen Hall, which was completed two years after Johnson’s first dictionary was published for Samuel Swinfen, according to the designs of Benjamin Wyatt, father of James, who helped preserve Lichfield Cathedral. They keep things close in this part of the world.

The Hall provides a great location for a pre-dinner aperitif on the cocktail terrace enjoying the view of the adjoining deer park. Both the interior and exterior of Swinfen Hall are quite magnificent. And, as with most ancient homes, it has a good yarn or two to tell.

The building’s south wing is of a much more recent design, built in the Edwardian period by Colonel Michael Swinfen Broun, for his daughter’s 21st birthday. The extension took three years to build, and perhaps tired of the weight, she decided to elope just a couple of weeks before the great event, which presumably put a bit of a dampener on the occasion.

However, the most famous inhabitant of the hall was Patience Swinfen, a parlour maid who married into the family and ended up being bequeathed the property upon the death of her father-in-law, her own husband already deceased. Unsurprisingly, her put out in-laws contested the will, and the Great Swinfen Case as it was known, became very much the talk of certain circles in Victorian times. The suit took seven years to resolve but in the end, Patience was rewarded, and a somewhat flattering portrait of her hangs in the reception hall she inherited.

Lichfield restaurants and pubs

For dinner, we had booked into Pom’s Kitchen a non-assuming place in the heart of Lichfield, close to the George Hotel. Reminiscent of the Wonky Table in nearby Derby, what Pom’s perhaps lacks in ambience – although I am partial to a tad of understatement – it more than makes up for in the quality of its fare and service.

To start, we had some tempura prawns which would have made many a crayfish blush in shame, so large were they, but cooked perfectly in a light batter to preserve their subtle flavour. So impressed was I that I asked where they were sourced. Devon came the response, while I admit I expected somewhere off the coast of Africa.

This was followed by the best swordfish I have had for years. Often, I find the dish either too salty or too dry, but this time it was chunky and quite divine. Once more enquiring where it came from, “Torquay”, was the reply. “You know that’s in Devon,” I responded. “Yes,” the waiter said with a smile.

Service was impeccable, and most of the food – except the seafood, this being middle England – is sourced locally. There is even a sign inviting people to bring in their own vegetables, which will be paid for at the market rate in vouchers to eat at Pom’s, like a medieval barter system.

The pubs in Lichfeld are renowned. Dr Johnson said of it, “I remember when all the decent people in Lichfield got drunk every night and we’re not the worse thought of.” It’s estimated that by 1830 Lichfield had 55 inns and 17 beer houses, approximately one hostelry for each 90 inhabitants.

The King’s Head on Bird Street, claims to be the oldest pub in Lichfield, dating back to 1408. Conveniently located across the street from Pom’s Kitchen, it is to here that I head for a swift pint of Marston’s Pedigree, brewed in nearby Burton, while my dinner companion enjoys her Aperol spritz on the street outside Pom’s chatting to the locals.

Lichfield Photo Gallery

National Memorial Arboretum

The King’s Head is also where the Staffordshire Regiment was formed. It is one of the many organisations whose dead are honoured in the National Memorial Arboretum, a short drive from town.

A pacifist at heart, I am not quite sure what to expect from the Arboretum. Fearing an overwhelmingly militaristic tone, I am reassured when our National Memorial Arboretum guide Paul explains that 30% of the memorials are civilian, ranging from the RNLI to the Fire Service and even the rail industry.

The arboretum was the idea of Commander David Childs who felt the need for a place to remember those who died in service after the end of the Second World War. Opened in 2001, the Arboretum now has more than 350 memorials spread over 150 acres of land.

It also has some 30,000 trees growing on a site that was treeless when Redland Aggregates, who rent the land to the National Memorial Arboretum for a peppercorn, had finished quarrying. You can sponsor a tree to be planted here as well if you wish. So popular has the site become, with some 300,000 visitors each year, that the National Memorial Arboretum is seeking to rent further land.

Some of the most notable memorials include the Never Forget Memorial Garden, where everlasting poppies are planted, the Twin Towers memorial which has fragments from the actual tower, and a memorial to those who died building the Burma railway, which has the actual tracks the men laid.

But to pick out individual memorials would be wrong, and the appeal of the place is to wander, or in our case take the buggy, around the place and soak in the atmosphere – and to remember.

Lest We Forget

This is very much at the heart of the main memorial – to the armed forces – that is the centrepiece of the National Memorial Arboretum. Designed by Liam O’Connor, the memorial consists of a huge marble wall upon which are inscribed the names of the 16,200 service men and women, who have perished either in action or in training accidents in the 47 conflicts Britain has been involved in since the end of Second World War.

These names are listed chronologically in alphabetical order without rank or gender, just as in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in France, as we are all equal in death. The sobering thought is the vacant space at the end of the list, to be filled with those yet to fall in service.

At the centre of the memorial are two bronze statues by Ian Rank-Broadley, one of which depicts a dead soldier being prepared for burial with his wife, parents and children looking on. This is no glorification of war, but an acknowledgement of the pain and suffering of those left behind.

National Memorial Arboretum Photo Gallery

Lichfield Festival

Each year the city holds a fantastic celebration of music, theatre, comedy, song and dance at the Lichfield Festival. The 2019 Festival was from 5-13 July. Details of the 2020 edition will be published here.

Lichfield Food Festival

There is also the award winning Lichfield Food Festival held each year over the August bank holiday weekend, with more than 320 specialist artisan food and drink traders showcasing their fare over three days.