On a trip to Whitby and the North York Moors, Mark Bibby Jackson encounters a small village steeped in popular culture, an iron-ore rush and two abbeys that would grace any part of the country.

The North York Moors has long held a fascination for me, ever since I first came here as a York University student in the mid-80s when the Miners’ Strike was in full flow, and the faces of anyone with a southern accent seemed fair game. The drive across the moors from Pickering to Whitby has to be one of the most dramatic in England, but until now I had never ventured off it onto the moors. An invitation to walk the Rail Trail through the North York Moors National Park seemed too good to miss.

Goathland: The Heartbeat of the North York Moors

Fans of the TV series Heartbeat will better know Goathland as Aidensfield, the fictional village that Nick Berry used to police, as the series was shot here. An old police car stands testament to its fame as do the hordes of tourists that descend upon the village each summer. As our host Clare Carr at The Farmhouse says, “you are more likely to find a police whistle as a loaf of bread in the shops here.” Clare travels to nearby Whitby for her shopping.

In recent years Heartbeat has taken a back seat to Harry Potter, as Goathland station was the setting for Hogsmeade station in the film Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. All this passes me by, as we narrowly avoid running over some particularly obstinate sheep who regard the road as theirs, reminiscent of my recent trip to the Faroe Islands, before arriving at the young sorcerer’s station. Clare’s husband Chris teaches me how to bully our ovine friends off the road.

North Yorkshire Moors Railway

The Rail Trail runs some three-and-a-half miles from Grosmont to Goathland along the original Whitby to Pickering line. George Stephenson, he of Rocket fame, was invited to construct the line that was opened in 1836 as a horse drawn tram way. However, the gradient between Goathland and Beck Hill – the Goathland incline – was too steep for horses and a system using counterbalanced water tanks was utilised instead. Steam was introduced in 1845, before the line was rerouted along what is now the current North Yorkshire Moors Railway line, in part to avoid the Goathland incline, although the descent out of Goathland station is still some 1 in 49, one of the steepest rail gradients in the UK rail network.

If you are planning on visiting the UK then consider reading our Essential Travel Guide to UK Holidays for the Over 40s?

To get to Grosmont, we take a steam train on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway from Goathland, along the tracks reopened in 1973 by the North York Moors Historical Railway Trust as a non-profit heritage railway. It now runs all the way from Pickering to Whitby. Chatting to one of the guards while waiting for my Thomas to arrive I learn the line has become somewhat of a roaring success, with 2 to 3,000 people visiting each day in the summer from as far afield as Canada and Australia. Some are Potter fans, others railway enthusiasts, and some Heartbeat devotees – it’s still shown on Saturdays in Australia – who realise there is little to do in Goathland once you have bought a policeman’s whistle.

During the Wartime Weekend when the spirit of World War II is recreated with volunteers dressed up as servicemen and women, factory workers and land army girls, over 30,000 people can flock to this little part of Yorkshire. The station has spared no expense in recreating a sense of the past – even the tickets are made especially at a printers in the Isle of Mull.

Our ride reminds me of my recent steam train journey in Radebeul, only this time we are passing through Yorkshire dales rather than Saxon forest, and there is no Cinderella’s Castle to await me upon my arrival. Instead, I take a quick cuppa in the tea rooms just down the road from the level crossing before returning to Goathland by foot.

North York Moors Walks

Before the advent of the railway, there was nothing much at Grosmont apart from farmland and the ruins of an abbey. But the discovery of iron ore here around the time the railway was built, led to a mini-iron rush, with blast furnaces rising to the skies and mines driven into the earth. By the 1890s the rush was over, and the village draper changed profession to an emigration agent facilitating one-way trips to the New World. Perhaps it is descendants of these emigrants that now return to travel along the line? However, Grosmont still has a cooperative dating back to those times formed by the miners, which celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2017, and is the oldest surviving independent cooperative in the UK.

As I walk along the old track through peaceful, green meadows, along a riverbank and through Buber Wood, it’s hard to imagine the billowing smoke that used to rise from furnaces here. Along the way, I pass the hamlet of Esk Valley where a row of cottages was built for workers along with a chapel in the 1860s. If you take the short diversion to Combs Wood, now a Site of Special Scientific Interest for its wildlife, you can see remains of old workshops, tramways and bridges that were built by the miners.

Shortly before the end of the trail I pass through the village of Beck Hill. The Birch Hall Inn was apparently a “hotbed of fighting and misbehaviour” when miners and navvies used to meet here. Now, it is one of the smallest pubs in Yorkshire, where the excellent beer is served through a small hatch, and the terrace, which is larger than the pub, affords tranquil views beside the Murk Esk. It makes for a perfect respite to summon sufficient strength to tackle the Goathland Incline back to the village.

A Walk Too Far

Pleasant and interesting though the walk was, it was not the wilds of the North York Moors. Chatting to my hosts Clare and Chris, I had resolved to spend the afternoon walking along the coastline from Staithes to Sandsend, which promised spectacular views. However, I had not allowed for Storm Ali.

Setting off from the town that has developed something of a reputation as an artistic community, I soon encounter a gale so strong even Cathy and Heathcliffe might have forgone traipsing the moors that day. As the rain started to slice sideways through my waterproofs I decide discretion is far preferable to valour, and instead drive to Sandsend for an excellent lunch at the much-recommended Bridge Cottage Bistro for the obligatory Whitby fish and chips, before strolling along the beach in a sandstorm that reminded me of Lawrence of Arabia.

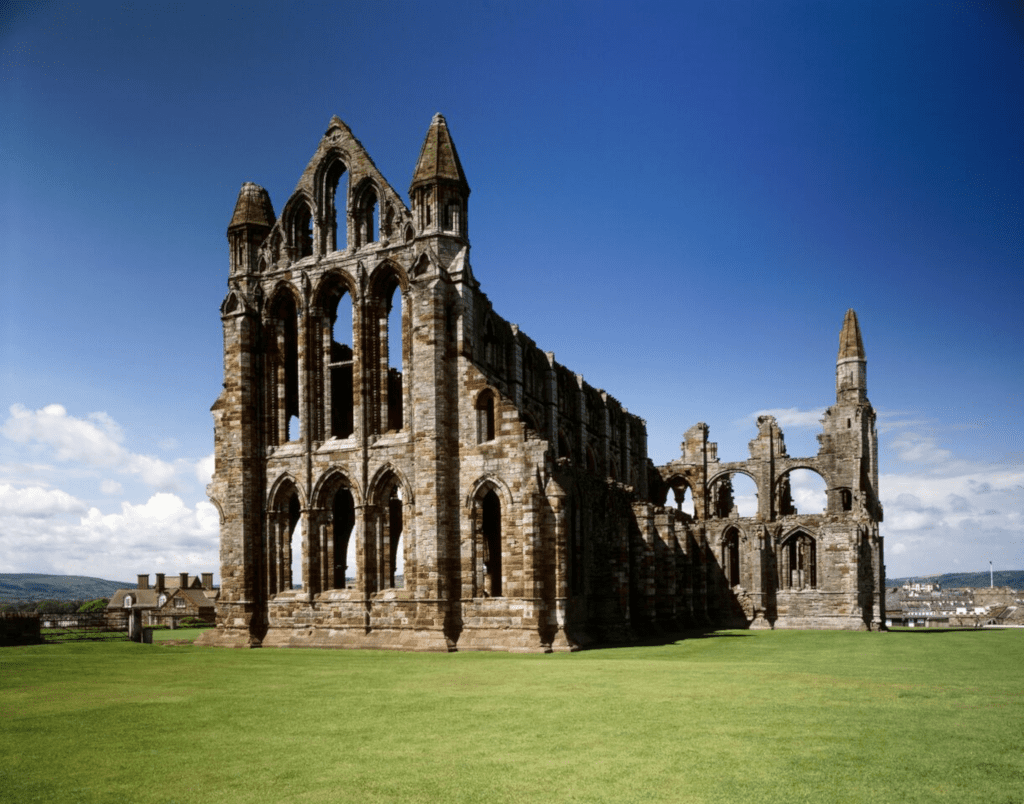

Whitby Abbey

Fortunately, the wind had abated the following morning as we return to the coast once more, this time to visit the magnificent Whitby Abbey. Some 199 steps lead from the town up to the Abbey, although it is far simpler to walk there from the headland car park.

The abbey was founded by Osway, King of Northumbria in 657, but then destroyed in the ninth century by the Danes. Rebuilt during William the Conqueror’s times, the buildings that remain date back to the 13th and 14th centuries. The abbey was dissolved with the monasteries by Henry VIII, and then passed into the hands of the Cholmley family who let it run into disrepair while living in some of the secular buildings.

Whitby Abbey is probably best known for its part in the Dracula legend – this is where the bloodsucking immortal landed when he visited England, in the Bram Stoker novel.

Wandering around the ruins rather than peeking over the surrounding walls, thus avoiding the English Heritage entrance fee, you get a sense of the weathered effect of the stonework, caused by its exposed position on this easterly headland facing the North Sea, as well as the subtle colouring of the stonework.

Set against blue skies and with sweeping views across Whitby and its bay to Sandsend, the abbey is at its best this morning. A weird calm descends upon us as we stroll amongst the ruins, and even a baby in her pushchair is quiet.

The adjoining museum has an interesting selection of artefacts dating back to Anglo-Saxon times.

Rievaulx Abbey

While Whitby Abbey might have the location, Rievaulx Abbey has substance. Founded by Walter Espec and Cistercian monks in 1132, at its height some 140 monks used to pray at this beautiful, tranquil setting on the banks of the River Rye, just outside the market town of Helmsley, across the North Yorkshire Moors from Whitby.

The most important Cistercian abbey in England, it was part of a trade network that stretched to Italy; fleeces from the abbey’s flocks were highly valued. First invaded by the Scots in 1322 and then ravaged by the Black Death (1348-9), Rievaulx declined in importance so that by 1380 only 15 monks remained. Finally, it was dissolved and dismantled in 1538, at the same time as Whitby Abbey, and sold to Thomas Manners, Earl of Rutland.

The magnificent East End of the church, where mass was celebrated at the high altar, reminds us how the abbey flourished in the early 1200s. Begun in the 1140s with a latter phase completed around 1220, it is more grandiose than earlier parts of the abbey, but though the architecture might be grand, the sculptures were restrained.

At the heart of the abbey is the communal cloister where the monks would meditate. Far vaster than Whitby, but with a tranquil rather than dramatic setting, here you can imagine the monks making their devotions in harmony with nature.

The museum has an interesting video demonstrating the Abbey’s timeline.

Helmsley Castle and Helmsley

Walter Espec was also Lord Helmsley, and the founder of Helmsley Castle, which dates back to the early 12th century. Though little of the original castle remains, the substantial defence mounds and ditches are impressive.

Another building to fall foul of Henry VIIIs marriage conundrum and dispute with Rome, Helmsley Castle was acquired by Edward Manners, Thomas’ grandson, in the late 16th century and remodelled as a Tudor mansion.

I scamper around the ruins of the castle eager to avoid the rain clouds that are gathering on the horizon, as we have to be in Beverley by nightfall. Thus, I fear I give the town of Helmsley, itself steeped in history and with a growing reputation as a foody town to rival neighbouring Malton, scant justice.

Once more I leave the North York Moors behind me without having walked across its heather strewn land. Still, there is always next time.

For more information on the North York Moors

Visit here

For information on the North Yorkshire Moors Railway

Visit here