Accepting an offer from the International Institute for Peace Through Tourism (IIPT) to visit Petra Jordan and Azraq Refugee Camp, Mark Bibby Jackson encounters a country with a rich history and a people doing all they can for the displaced in the region.

“Where is it?” I ask our guide Mohammed. “There,” he points to the narrow stretch of water barely wider than a country stream. “That’s the River Jordan?” A row of buoys that would not look out of place in a municipal swimming pool demarks the border between Jordan, where I stand, and Israel barely ten metres away. In some ways this epitomises the trouble this region has faced since time in memoriam; too close for comfort.

I am coming towards the culmination of my week-long visit to the country, yet still it never fails to surprise. We have just walked from the deserted car park through the place where legend has it that John baptised Jesus – a couple of Russians dressed in white re-enact the moment – while I dip my feet in the cooling waters. Opposite us, hordes of tourists on the Israeli side pose on their bank snapping away with their selfie sticks, oblivious to the moment. Jericho is barely visible in the distance.

An oasis of peace in the troubled Middle East region, Jordan has assumed a traditional role of accepting refugees.

“We keep our doors open to our neighbours,” HRH Princess Dana Firas, the President of the Petra National Trust, had informed me upon our arrival.

The last century saw successive waves of refuges from Chechens to Palestinians – some of whom have lived here for over 60 years – and more recently Syrians.

“These waves of people have enriched our nation,” the Princess continues in a sentiment sadly absent from much of the rhetoric in the West. “We benefit as well.”

But such philanthropic responsibility comes at a cost, and the oil-bereft country is largely reliant on its tourism industry, which has seen a 65% drop since 2010, largely due to the intensification of troubles in the region.

I half expect a bunch of elderly missionaries, bibles in hand, to greet me at the breakfast buffet over grace

“Tourism is an invaluable part of our economy,” the Princess says.

Which in part explains why I – a committed atheist – am sat dipping my toes in the waters where, according to a book I view as fable, the son of a god, I do not recognise, was blessed in a ceremony, I do not appreciate. For, I had accepted an invitation from the International Institute for Peace through Tourism (IIPT) to go on a trip to Jordan which would take me to the refugee camps in the north as well as to the more familiar tourist highlights of Wadi Rum and Petra to the south, and the Dead Sea.

Following in the Footsteps of Lawrence of Arabia

It all started perfectly conventionally. Landing late, I take a taxi to my hotel and fail to sleep until my alarm informs me it’s time to ‘awaken’ and meet my companions for the week. I half expect a bunch of elderly missionaries, bibles in hand, to greet me at the breakfast buffet over grace. Instead, I meet a mix of Australians, one of whom was New Zealand-Chinese, another German and a third of Irish descent, that epitomises the cross-cultural nature of the Antipodean nation; all united by a John Lennon inspired approach to tourism.

Forewarned not to expect much from the capital Annan, I am pleasantly surprised to discover in the Temple of Hercules and the largest Roman theatre in Jordan, sites that, while hardly comparable with the delights of Ancient Greece, are a pleasant introduction to the kingdom, especially as it was still morning and the temperature cooling. Few linger in Amman, and we are no exception, departing the following day, after the formalities of our meeting with HRH concluded.

A dust storm, worthy of T.E. Lawrence descends upon us as we head south along the highway, passing through barren terrain it is inconceivable that this used to be replete with trees, cut down first to melt copper and then to build the now dormant railways. Apparently, the Ottomans also imposed a tax on trees – a measure Trump might still adopt in his climate change denial mania.

There is an unworldly atmosphere to the place, as if we have wandered onto a lunar landscape

Sadly, you can see more roadside litter than trees now – with Mohammed quipping that the plastic bag is the national bird of Jordan.

Eventually, as we approach Wadi Rum the flat landscape relents and a vast valley unfolds before us, with sandstone hills emerging in the distance. We pass the entry to the national park and reserve, where checking in is both obligatory and advisory. Mohammed informs me that two French tourists died in a mountaineering accident last year having failed to check in; nobody knew they were missing and their bodies were discovered days later.

There is an unworldly atmosphere to the place, as if we have wandered onto a lunar landscape, the ideal setting for the latest episode in the Star Wars saga, but it is another film that has made this region famous. This is the land of Lawrence of Arabia, and after a lunch at the Captain’s Desert Camp where Mohammed Ali, not the boxer but a blind musician, entertains us with his play of the owd allute – a type of lute – and song, we set off into the valley where Lawrence and Prince Abdullah slept.

Our accommodation is as modest as theirs had been, traditional Bedouin tents with little allowance for the western tourist mindset; the lack of lighting caused something of a ruckus with my companions. While some take a short sunset ride on a camel, our sole host prepares a meal in the zarg – a hole in the ground where a couple of chickens and a side of lamb are roasted along with some vegetables – and I wander off into the brilliant sunset.

At night, so far from the intrusion of civilization, the absence of light allows for the most amazing stargazing, and the deafening silence is only broken by the crackle of the wood burning on the bonfire.

Youthful Bedouins ride their horses through the canyon like outlaws fleeing a posse in the Wild West

Petra Jordan: a Matter of Timing

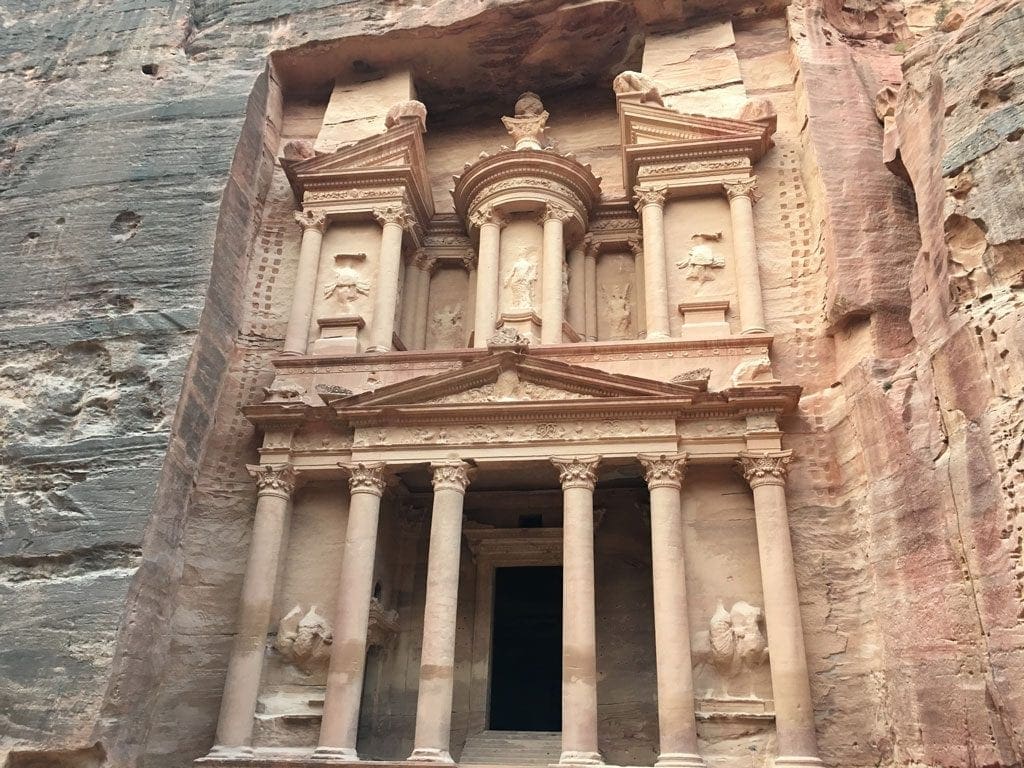

Petra is the Greek for rock. As I walk through the valley towards the Treasury building, I can see why the most famous archaeological site in Jordan– and one of the Seven Modern Day Wonders of the World – was given the name. The Nabataeans moved here in part due to the sheer immensity of the rock walls that would successfully defend them from hostile incursion. But it also allowed them to carve their statues and temples to both their gods and the dead. According to Mohammed, the ancient inhabitants of the place were more concerned with life than death.

And for this I guess we should be thankful. For the UNESCO World Heritage Site is truly a wonder to behold.

The Petra National Trust has various schemes, including a cultural education programme at schools in the area, which educates people about the site’s culture, environment and traditions, as well as adopting measures to protect the monuments from erosion. Vehicles are banned from the site, so those wishing to avoid the lengthy walk have to ride a horse or sit in a cart, but this does not stop the sound of jet planes flying overhead as part of US-Jordanian military exercises – further reminder if any is needed of the nearby troubles.

As with good comedy, the trick to Petra lies in the timing. By the time we reach the first main building – the Treasury Building that was never used as a treasury – the area is overrun with tourists and locals plying their trade, apparently there is a cruise ship in town – despite Petra being far from the sea. Youthful Bedouins ride their horses through the canyon like outlaws fleeing a posse in the Wild West.

Fortunately, I have time on my hands and remembering that Princess Dana had informed me that the best time to visit is at 6am, I can return to Petra later on my trip and, torch in hand, retrace my steps through the canyon. This time I arrive at the Treasury as the sun is rising, and find myself alone.

The next hour or so, I wander through the valley of temples and statues in perfect isolation, able to appreciate the majestic buildings without the click of horses’ hooves or camera shutters. Eventually, I make my way up to the viewpoint behind the Monastery and look down upon the valley below. I even regret being on my own this time as there is nobody to share the moment with.

The only person I do meet is a fellow 40-something Brit, Jon Poulter, who is trekking the Jordan Trail. Twenty-five days of “full on stuff” according to the veteran of similar exploits across Australia and Mongolia.

“I’ve just shed a tear it’s so awesome,” the hard man from Devon confessed upon seeing Petra for the first time. “I just want as many experiences like that as possible.”

The accommodation is clearly designed to be temporary, although many have stayed here for years

The experience I encounter in the north of the country is one that will live with me, although hopefully I will not repeat again.

Azraq Refugee Camp

Azraq Refugee Camp is close to the Syrian border. Iraqi refugees first came here in 1992, although the camp is now used to house Syrians displaced by the current problems in their homeland.

The main purpose of our visit was for the IIPT delegation to visit a school run by the Al-Jandaweel Baptist Church and to hand out much needed materials, both to the school kids and their parents. But before this, we are permitted to visit the refugee camp, which required multiple permits as it is strictly off-limits for normal tourists.

It is my first visit to such a camp, and I have to admit to being surprised by how humane the conditions were, and how clean. However, whole families are crowded into corrugated housing that must get extremely hot in the summer. The accommodation is clearly designed to be temporary, although many have stayed here for years.

Briefly I am allowed to wander freely on my own, and I am drawn to the most amazing mural created by the refugees, before I am invited in for a coffee by Abdullah, who lives here along with his family. There is a dignity in their behaviour that reminds me of a similar experience in Nuwakot, Nepal, where I shared lunch with one of the women there whose own home had been destroyed by the 2015 earthquake.

The following day, we visit the school, and I feel guilty that our intervention puts paid to any idea the teachers have of educating their students. Although, the school is run by a Baptist church, the pupils are Muslim – Druze and Bedouin – often travelling from as far as 70km away. There is no bible being forced down the throat of the children, and some of the classes are co-educational.

Afterwards we visit the parents of one of the girls there; a Syrian family from the outskirts of Damascus. They had escaped their war-torn home four years ago in a sheep truck. Having lived in the refugee camp for two years, they fled illegally to a small house in Azraq, where the family of seven live, one of whom works night shifts in one of the local restaurants, that clearly turns a blind eye towards work permits.

They treat us to tea as we sit in their living room, and the mother of the family explains how much she pines to be back in Syria.

“When the war stops I want to return home,” she says. “My house is still standing so hopefully I can go back. But even if I have to live in a tent, I want to return to my country.”

In travelling, the least anticipated experiences can prove the most rewarding

If Azraq is a cruel reminder of man’s inhumanity towards each other, then the Dead Sea provides a lesson on our destruction of the environment.

A Dead Sea Mud Pack

At 427 metres below sea level, the area around the Dead Sea is the lowest land point on earth. It’s also retreating by about a metre a year, as water is being diverted to Israel, dammed and increasingly used to power industry, as well as the impact of climate change.

People come here to laze in the salt waters and smother themselves in mud; both of which are said to be good for the skin. Leaving the sanctuary of the Movenpick where I am staying, I walk down to the shore and into the waters. After a while bobbing up and down on the surface – the salt water means that even the least buoyant can float – I try to scramble to the shore, only to discover that the same qualities that make flotation easy discriminate against graceful departure.

Eventually I manage to reach dry land, my dignity left dead in the sea. Then I apply the mud, as much as possible, as instructed by my mud-application-instructor-cum-life-guard. And I sit and wait while the sun dries the mud on my body, before once more returning to the salt waters to wash away my sins.

A cynic by nature, I’m amazed later that evening to discover my skin tingling as if the water had cleansed all its perfections along with the mud. Tonight at least I feel totally rejuvenated.

I have one last trip to recount on this most unusual journey.

Taking a taxi up from the Dead Sea back to Petra for my dawn excursion, we pass through a mountain range, where we stop en route for a coffee and to enjoy the view. In the distance, I can hear trucks passing in and out of a potash factory, and I can just make out the Dead Sea beyond the haze. Eagles drift by. My driver sits and contemplates.

In travelling, the least anticipated experiences can prove the most rewarding. I am not expecting anything from this drive, but the view across the mountains to the Dead Sea, and passing through small villages with their deserted old stone houses, gives me a snapshot of Jordanian life that I will cherish for a long time. In Jordan, there is a totally relaxed attitude to life, as if time itself has become lost in translation.

Petra Jordan Weather

Jordan’s climate is classified as ‘hot and dry’. In the summer, especially around August temperatures can rise to 40C. However winters tend to be colder dropping to 5C to 10C in January. Most of the rain falls between November and March, when there can be flash floods. June to August is often dry. The east of the country has a dessert climate.

Petra Jordan Hotels

To book a hotel at Petra Jordan or elsewhere in the country, click here. Any booking you make helps support this website without affecting your price.